Essential Techniques for Machining Stainless Steel 316L

TL;DR

Machining stainless steel 316L is notoriously difficult due to its high toughness, low thermal conductivity, and rapid work-hardening properties. Success hinges on a combination of factors: using extremely rigid machine setups, employing sharp and durable cutting tools like coated carbides, applying generous amounts of coolant, and adhering to specific machining parameters. The key is often to use slower cutting speeds but higher, consistent feed rates to maintain a continuous cut and prevent the material from hardening during the process.

Understanding 316L Stainless Steel: Properties and Machinability Challenges

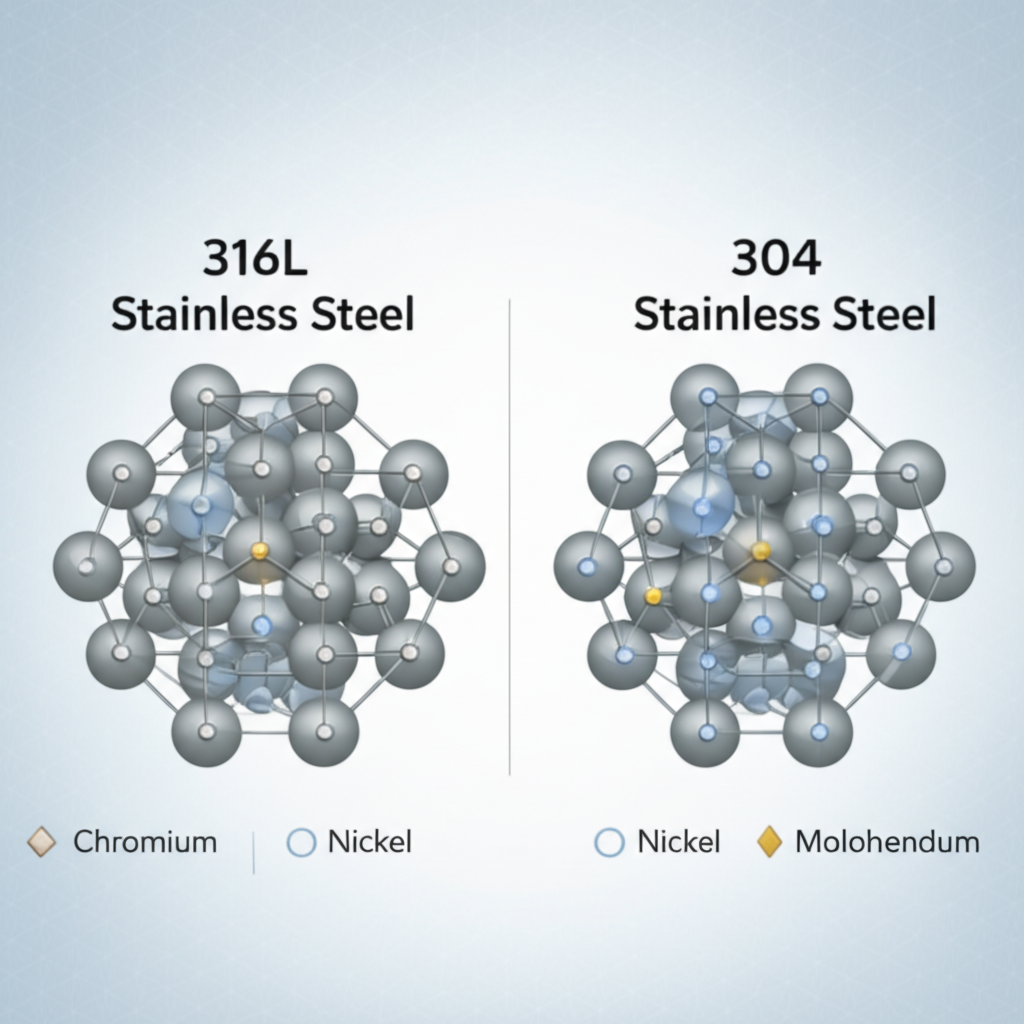

Stainless steel 316L is an austenitic chromium-nickel-molybdenum alloy prized for its exceptional corrosion resistance, especially in chloride-rich environments like marine or chemical processing applications. The 'L' in 316L signifies a lower carbon content (typically below 0.03%) compared to standard 316 steel. This reduction in carbon enhances its weldability and further improves its resistance to corrosion after welding. However, the very properties that make 316L so durable also present significant hurdles in machining.

The primary challenge stems from its austenitic structure, which makes the material both tough and ductile. This combination leads to a 'gummy' machining characteristic, producing long, stringy chips that can wrap around tooling and interfere with the cutting process. Furthermore, 316L has poor thermal conductivity. Heat generated at the cutting edge does not dissipate quickly through the workpiece, instead concentrating in the tool, which can lead to premature tool wear, deformation, and even catastrophic failure.

Perhaps the most significant obstacle is its tendency to work-harden rapidly. When the cutting tool engages the material, the mechanical stress of the operation hardens the surface layer almost instantly. If the subsequent cut is not deep enough to get under this hardened layer, the tool will be forced to cut through a much harder material, dramatically increasing tool wear and making consistent machining nearly impossible. This phenomenon requires a strategic approach to feeds and depths of cut to stay ahead of the hardening effect.

A common question is whether 316L is easier to machine than standard 316. The lower carbon content in 316L gives it a slight edge in workability and formability, making it marginally easier to machine than its standard 316 counterpart. However, both are considered to have poor machinability ratings, with some sources like 3ERP noting that 316 has one of the poorest ratings among stainless steels, requiring specialized tools and techniques.

Optimal Machining Parameters: Speeds, Feeds, and Tooling

Achieving success in stainless steel 316L machining requires a data-driven approach to speeds, feeds, and tool selection. Generic parameters often lead to failure; precision is key. The goal is to balance material removal with heat management and the prevention of work hardening. This often means departing from conventional wisdom used for carbon steels and adopting a more deliberate strategy.

Cutting speeds must be carefully controlled. Due to the material's poor thermal conductivity, excessive speed generates heat faster than it can be carried away, leading to tool failure. For turning operations, recommended cutting speeds typically fall in the range of 490-660 SFM (150-200 m/min), while milling operations are slower, around 310-410 SFM (95-125 m/min), according to datasheets from resources like Machining Doctor. In contrast, feed rates must be aggressive and, most importantly, consistent. A high, continuous feed ensures the cutting edge is always getting beneath the previously work-hardened layer.

Tool selection is non-negotiable. Standard high-speed steel (HSS) tools will not last long against 316L. The industry standard is to use carbide inserts, often with advanced coatings like Titanium Aluminum Nitride (TiAlN) or Aluminum Titanium Nitride (AlTiN). These coatings provide a thermal barrier, increase surface hardness, and reduce friction. The geometry of the cutting edge is also critical; a sharp, positive rake angle helps to shear the material cleanly rather than plowing through it, reducing cutting forces and heat generation.

Below is a summary table of recommended starting parameters for common operations on 316L stainless steel. These values should be adjusted based on specific machine rigidity, tool holder type, and coolant application.

| Machining Operation | Cutting Speed (SFM) | Cutting Speed (m/min) | Primary Tooling Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Turning | 490 - 660 | 150 - 200 | CVD/PVD Coated Carbide Inserts |

| Milling | 310 - 410 | 95 - 125 | PVD Coated Carbide End Mills |

| Drilling | 230 - 330 | 70 - 100 | Coated Solid Carbide Drills |

| Grooving/Parting | 200 - 390 | 60 - 120 | PVD Coated Carbide Inserts |

Proven Techniques and Best Practices for Machining 316L

Beyond speeds and feeds, several practical techniques are essential for successfully machining 316L stainless steel. These best practices focus on creating a stable cutting environment and actively mitigating the material's challenging properties.

- Ensure Maximum Rigidity: Any vibration or chatter during the cut will be amplified by the toughness of 316L, leading to a poor surface finish and rapid tool wear. Use the most robust machine available, secure the workpiece firmly, and minimize tool overhang by using the shortest possible tool holders and cutting tools.

- Utilize High-Pressure Coolant: Coolant is not optional; it is critical. A constant, high-volume flood of coolant is needed to extinguish heat at the cutting zone and effectively flush chips away from the workpiece. For operations like deep drilling or slotting, high-pressure, through-spindle coolant is highly recommended to prevent chip packing and tool failure.

- Maintain a Continuous Cut: Never allow the tool to dwell or rub against the surface without actively removing material. This action generates significant friction and will immediately work-harden the surface, making re-entry for the next pass extremely difficult. Program tool paths to ensure constant engagement wherever possible.

- Employ the 'Slower Speed, Higher Feed' Rule: A common rule of thumb for stainless steels is to reduce the cutting speed while increasing the feed rate. As discussed, this strategy helps manage heat generation while ensuring the cutting edge gets under the hardened layer created by the previous pass.

- Use Sharp, Positive Rake Tooling: A sharp cutting edge is paramount for shearing the material cleanly. A dull tool will plow and push the material, increasing cutting forces and exacerbating work hardening. Positive rake geometries reduce cutting pressure and help form a cleaner chip, improving both tool life and surface finish.

For complex parts or projects with tight tolerances, the combination of these challenges can be daunting. In such cases, leveraging the capabilities of a specialized service can be beneficial. For projects requiring exacting precision, services like XTJ CNC Machining Services utilize advanced 4 and 5-axis centers specifically configured to handle these demanding materials effectively.

Comparative Analysis: Machining 316L vs. 304 Stainless Steel

For many engineers and machinists, 304 stainless steel is a more familiar material. As the most widely used stainless steel, it serves as a useful benchmark for understanding the specific challenges of 316L. While both are austenitic and prone to work hardening, key differences in their composition lead to distinct machinability characteristics.

The primary difference, as noted by manufacturing experts at Geospace Technologies, is that Type 304 is generally more machinable than 316. The addition of molybdenum in 316L, which gives it superior corrosion resistance, also increases its toughness and high-temperature strength, making it more difficult to cut. The nickel content in both materials contributes to their toughness and ductility, but the combination with molybdenum in 316L tips the balance towards lower machinability.

Consequently, machining 304 allows for slightly higher cutting speeds and may be more forgiving of minor imperfections in setup or tooling. In contrast, 316L demands a more rigorous and optimized approach, as it is less forgiving and work-hardens more severely. Tool wear is typically more pronounced when machining 316L compared to 304 under similar conditions. The choice between the two often comes down to a trade-off between the application's corrosion resistance requirements and the manufacturing cost and complexity.

| Property | Stainless Steel 316L | Stainless Steel 304 |

|---|---|---|

| Machinability | Poor | Fair (Better than 316L) |

| Corrosion Resistance | Excellent (especially against chlorides) | Good |

| Key Alloying Elements | Chromium, Nickel, Molybdenum | Chromium, Nickel |

| Work Hardening | Very High | High |

| Common Applications | Marine hardware, chemical processing, medical implants | Kitchen appliances, architectural trim, food equipment |

Key Takeaways for Successful 316L Machining

Machining 316L stainless steel is a demanding task, but it is far from impossible. Success is built on a foundation of understanding the material's unique properties and respecting its limitations. The path to a perfect finish and optimal tool life is not about speed, but about control. By prioritizing rigidity in the machine and setup, you create a stable platform that minimizes harmful vibrations.

The selection of appropriate carbide tooling with modern coatings is a critical investment that pays dividends in performance and longevity. This must be paired with an aggressive and intelligent use of coolant to manage the intense heat generated at the cutting edge. Finally, adhering to a disciplined strategy of slower speeds and higher, continuous feeds allows you to stay ahead of the material's rapid work-hardening tendency. By integrating these principles, machinists can transform one of the most challenging materials into high-quality, precision components.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Is 316L easier to machine than 316?

Yes, 316L is generally considered slightly easier to machine than standard 316 stainless steel. The 'L' stands for low carbon, and this reduced carbon content improves the material's workability and formability. While both grades are challenging to machine due to their toughness and work-hardening characteristics, the lower carbon in 316L provides a marginal advantage in machining operations.

2. What is the hardest stainless steel to machine?

While 'hardest' can be subjective, austenitic grades like 316 stainless steel are consistently cited as having among the poorest machinability ratings. This is primarily due to their high toughness and tendency to work-harden rapidly during cutting, which causes significant tool wear. Other specialty or precipitation-hardening grades can also be extremely difficult, but among common grades, 316 is a top contender for being the most challenging.

-

Posted in

316l stainless steel, cnc machining, machining parameters, metal fabrication, Work Hardening