CNC Machining Tolerances: Balancing Precision and Cost

TL;DR

CNC machining tolerance is the acceptable, permissible variation in a physical dimension of a part from its intended value on a blueprint. Correctly specifying these tolerances is a critical engineering task, as it directly governs the component's fit, function, and final manufacturing cost. Mastering tolerances ensures parts assemble correctly without being unnecessarily expensive or time-consuming to produce.

What Are CNC Machining Tolerances?: A Foundational Definition

In the world of precision manufacturing, no process is perfectly exact. CNC machining, while incredibly accurate, is subject to minute variations. CNC machining tolerance defines the acceptable range for this variation. It is the total amount a specific dimension is permitted to vary from the nominal or target value. Essentially, it's not a single value but a range, establishing the upper and lower limits that a finished feature must fall within to be considered acceptable. If a part's measurement falls outside this range, it is typically rejected.

These variations are often incredibly small. For example, a standard tolerance might be around ±0.127mm (±0.005 inches). To put that into perspective, the average human hair is about 0.05mm to 0.07mm thick. This means a standard machining tolerance can be as narrow as the width of two human hairs. This level of precision is what allows for the creation of complex, interchangeable parts that are the bedrock of modern technology, from aerospace components to medical devices.

Understanding tolerance is fundamental for designers and engineers because it serves as the language to communicate the required level of precision to the machinist. It dictates how a part will fit with other components in an assembly and how it will perform under operational stress. Without a clear understanding and application of tolerances, manufacturing would be a game of chance, leading to wasted materials, failed assemblies, and unreliable products.

The Importance of Tolerances: Balancing Cost, Fit, and Function

Specifying tolerances is a crucial balancing act between performance requirements and manufacturing costs. Every decision on a blueprint carries financial and functional implications. Overly tight tolerances can skyrocket costs unnecessarily, while tolerances that are too loose can lead to product failure. The key is to find the optimal balance that ensures functionality without inflating the budget.

A primary function of tolerance is to guarantee the proper fit and function of mating parts in an assembly. For components that must fit together—like a shaft in a bearing or a pin in a hole—the relationship between their dimensions is critical. Tolerances ensure that, despite small manufacturing variations, there will always be the correct amount of space (clearance fit) or interference (press fit) for the assembly to work as designed. Tighter tolerances lead to more consistent and reliable performance, which is non-negotiable for critical applications in industries like medical and aerospace.

However, this precision comes at a price. Achieving tighter tolerances demands more from the manufacturing process. It often requires more advanced and expensive machinery, slower cutting speeds, specialized tooling, and more frequent, time-consuming inspection processes with sophisticated metrology equipment. Each of these factors adds to the overall cost and lead time of a part. Therefore, a core principle of efficient design is to specify the tightest tolerances only where they are functionally necessary and to allow for looser, more economical tolerances on non-critical features.

| Aspect | Tight Tolerances (e.g., ±0.025mm) | Loose Tolerances (e.g., ±0.25mm) |

|---|---|---|

| Function & Fit | High precision, ensuring consistent and reliable assembly for critical components. | Suitable for non-critical features where fit is not a primary concern. |

| Manufacturing Cost | Significantly higher due to advanced machinery, slower speeds, and higher scrap rates. | Lower cost due to faster machining, less scrap, and simpler inspection. |

| Lead Time | Longer, as more time is needed for machining, setup, and quality control. | Shorter, enabling faster production cycles. |

| Ideal Application | Aerospace components, medical implants, high-performance engine parts. | Covers, enclosures, and general structural components. |

Key Types of Machining Tolerances Explained

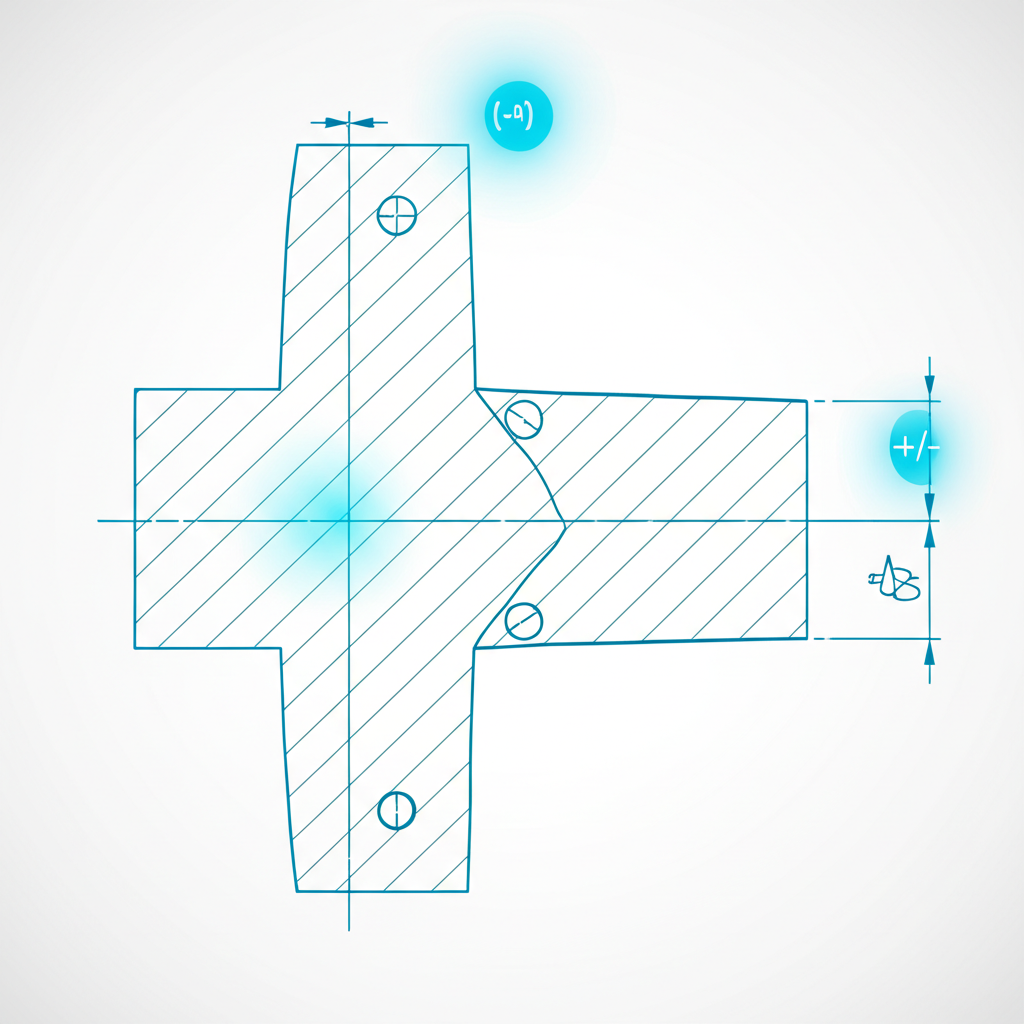

To communicate design intent clearly, engineers use several types of tolerances, each serving a specific purpose. These can be broadly categorized into dimensional tolerances, which control size, and geometric tolerances, which control form, orientation, and location. Understanding these types is essential for creating accurate and manufacturable designs.

The most common are dimensional tolerances, which define the acceptable size limits for a feature. They include:

- Bilateral Tolerance: This allows variation in both positive and negative directions from the nominal dimension. It is often symmetrical, such as 20.00mm ±0.05mm, meaning the final part can range from 19.95mm to 20.05mm.

- Unilateral Tolerance: This permits variation in only one direction from the nominal size. For example, 20.00mm +0.10/-0.00mm. This is useful for situations where a part must not exceed a certain size to fit into an assembly, ensuring it is never oversized.

- Limit Tolerances: This method avoids plus/minus notation by explicitly stating the maximum and minimum permissible dimensions. For example, a dimension might be written as 20.05mm / 19.95mm. This format is very clear and removes any ambiguity for the machinist.

Beyond simple size, Geometric Dimensioning and Tolerancing (GD&T) provides a more sophisticated and comprehensive symbolic language to define the tolerance of a part's features. As detailed by standards from the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME), GD&T controls not just size but also characteristics like form (flatness, straightness), orientation (perpendicularity, parallelism), and location (position, concentricity). For example, a flatness callout ensures a surface is smooth and even within a specified range, which is critical for sealing surfaces. GD&T is indispensable for complex parts where the relationship between features is as important as their individual sizes.

Understanding Standard Tolerance Charts (e.g., ISO 2768)

To streamline the design process and avoid cluttering drawings with tolerances for every single dimension, engineers often rely on standard tolerance systems. These systems provide a set of default tolerances that apply to any dimension on a drawing that does not have a specific tolerance indicated. One of the most widely used standards is ISO 2768, which simplifies tolerancing for general machined parts.

The purpose of a standard like ISO 2768 is to establish a baseline for manufacturing precision that is acceptable for general use. It helps ensure consistency and reduces the need for designers to calculate and specify a tolerance for every non-critical feature, saving time and preventing errors. The standard is typically divided into two parts: one for linear and angular dimensions (ISO 2768-1) and another for geometric tolerances (ISO 2768-2).

ISO 2768-1 specifies tolerance classes for different levels of precision, commonly designated by letters. For linear dimensions, these classes are often 'f' (fine), 'm' (medium), 'c' (coarse), and 'v' (very coarse). A machine shop might adopt ISO 2768-m as its standard, meaning all untoleranced dimensions will be produced according to the 'medium' class specifications. The specific tolerance value depends on the nominal size of the feature, with larger dimensions being allowed a larger variation.

| Nominal Size Range (mm) | Permissible Deviation (± mm) |

|---|---|

| 0.5 up to 3 | ±0.1 |

| Over 3 up to 6 | ±0.1 |

| Over 6 up to 30 | ±0.2 |

| Over 30 up to 120 | ±0.3 |

| Over 120 up to 400 | ±0.5 |

By referencing a standard like this on a drawing, designers and machinists establish a clear, shared understanding of the required precision for general features, allowing them to focus their attention on the critical dimensions that require specific, tighter tolerances.

Practical Tips for Specifying and Achieving Tolerances

Effectively specifying and achieving the correct CNC machining tolerances requires a thoughtful approach that considers both the design intent and the realities of the manufacturing process. Applying tolerances incorrectly can lead to unnecessary costs or non-functional parts. Here are some practical tips for engineers and designers to follow.

- Tolerance Only What Is Critical: The most important rule is to apply tight tolerances only to features where they are absolutely necessary for the part's function, such as mating surfaces, bearing bores, or critical alignment features. Over-tolerancing non-critical surfaces adds significant cost with no functional benefit.

- Use the Loosest Tolerance Possible: Always start with the loosest tolerance that will still allow the part to function correctly. This is the most cost-effective approach. A component's function should be the primary driver for tolerance selection, not an arbitrary desire for precision.

- Consider Material Properties: The material being machined has a significant impact on the achievable tolerance. Harder materials are often more dimensionally stable and easier to machine precisely. Softer materials, like some plastics, can deform under tool pressure or expand with heat, making tight tolerances more challenging and expensive to hold.

- Understand Manufacturing Process Limitations: Different CNC machining processes have different levels of inherent accuracy. A standard 3-axis mill has different capabilities than a high-precision 5-axis machine or a lathe with live tooling. Be aware of the capabilities of the processes you intend to use.

- Communicate Clearly with Your Machining Partner: Open communication with your manufacturing provider is key. Discuss critical features and your design intent to ensure they understand the requirements. An experienced partner can often provide feedback on how to optimize your design for manufacturability and cost. For projects requiring high precision, working with a capable service is essential. For example, some providers like XTJ CNC Machining specialize in advanced 4 and 5-axis machining and can handle tolerances down to +/- 0.002mm across a wide range of materials.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is a standard tolerance for CNC machining?

While it varies by machine shop and material, a common standard tolerance for CNC machined metal parts is approximately ±0.125mm (±0.005 inches). For plastics, it may be slightly looser. Many shops default to a standard like ISO 2768-m (medium) if no specific tolerances are provided on the drawing.

2. What is the difference between tolerance and allowance?

Tolerance is the permissible variation in the dimension of a single part. It defines how much larger or smaller a feature can be and still be acceptable. Allowance, on the other hand, is an intentional difference between the dimensions of two mating parts. It defines the minimum clearance or maximum interference between them and determines the type of fit (e.g., clearance, transition, or interference fit).

3. How do you read tolerance symbols on a drawing?

Dimensional tolerances are typically shown as a nominal size followed by a plus/minus value (e.g., 10.0 ±0.1), as upper and lower limits (e.g., 10.1/9.9), or through a standard tolerance block. Geometric Dimensioning and Tolerancing (GD&T) uses a complex system of symbols within a feature control frame to define tolerances for form, orientation, and location. Each symbol represents a specific characteristic, such as flatness (a parallelogram), perpendicularity (an upside-down T), or true position (a crosshair symbol).

-

Posted in

cnc machining, engineering design, GD&T, machining tolerances, manufacturing